Developmentally Appropriate Risk Taking Behavior: Finding the Balance Between Overprotection & Nonchalance

Developmentally Appropriate Risk Taking Behavior: Finding the Balance Between Overprotection & Nonchalance

By Jessica Taylor-Pickford, LCSW, IMH-E (Mentor Clinical)

February 2021

Early childhood experts have long known that young children typically learn through the exploration of their environment, and that they are much more successful in doing so if they feel encouraged and supported by their caregivers. Often times, this exploration includes behaviors that parents and caregivers deem to be risky, such as climbing, throwing, jumping, playing with objects that are not meant for children, or playing with things in ways they were not meant to be played with.

Risk taking behaviors and risky play have a number of benefits for young children. If done well, it can help young children build both confidence and concrete skills. Allowing children to take small risks sends the message “I trust you” and offers them the opportunity to learn not only by practicing new skills in an incremental way, but through minor failures they might otherwise not be allowed to experience. Small failures actually promote resilience, giving a young child the opportunity to practice regulating their emotions and trying again. For example, your little one might better figure out how to stop themselves on a scooter when they are going too fast (a key self regulatory skill) if actually given the opportunity to go a bit faster than they (or we) are comfortable with. Over time, they will develop an awareness of appropriate speed or incline. Perhaps with a few falls along the way, they will learn to pick themselves up, get the comfort they need from a caregiver, and return to try again.

While I feel driven to support the exploration of my young children, I know those situations become fraught when their behaviors become too risky (or sometimes too messy—but we’ll save that discussion for another day). Do I stop them, or hold my breath and hope for the best? It can be difficult to find a balance between overprotection that disrupts healthy exploration and nonchalance. There is a wide space between both approaches, and the stance you take is likely dependent on both you and your child. Here are a few ideas:

Take Time to Analyze the Risks and Benefits of a Certain Behavior Beforehand

Of course we want our babies and toddlers to be safe, but there are times we miscalculate the risks of a situation based on our own fears about worst case scenarios. Ask yourself not only what the worst thing that could happen would be, but also spend time wondering how you and your child might benefit too.

Consider Your Child

Every child is different, with different skills and abilities, at various developmental levels. It can be helpful to think about what your child can do and what areas you might need to support your child in taking steps towards learning.

For example, the first time a child climbs a ladder, they may need help thinking through hand and foot placement on the low rungs, and your support beneath them as they get higher. Over time, once the skill is mastered, you may find yourself able to provide fewer cues and less support. Next thing you know they’re scaling the playground safely and confidently.

Assess the Environment

You know your neighborhood, your playground, your child, and your comfort level best. Take these things into account before you venture out into the community for an outing.

Knowing how a gate latches, whether the playground equipment is developmentally appropriate, and the proximity to the road are always things I keep in mind for park exploration. It sets us up for success because I am already prepared with limits in mind and can be more free to focus on safe exploration.

Use These Moments as Opportunities for Learning

Sometimes we are so overwhelmed by our child’s behavior that it can be difficult to find an opportunity to teach in the moment. We just need whatever it is to stop. We distract, we cajole, we remove things, we move our children. Unfortunately, that does not allow our child the opportunity to learn a limit or skill associated with making any behavior less risky.

If we are able to think on our toes, not just about stopping a risky behavior, but rather what a child would need to learn to do it safely, offers opportunities for growth and learning. For example, if my toddler is throwing something breakable, let them see and hear the sound it makes when it hits the floor. In my gut, I want to immediately say “stop throwing” and remove the item. Instead, I can use the opportunity to offer him something less breakable but still crashworthy, letting him know that it will make a different sound when it hits the ground. Win-win.

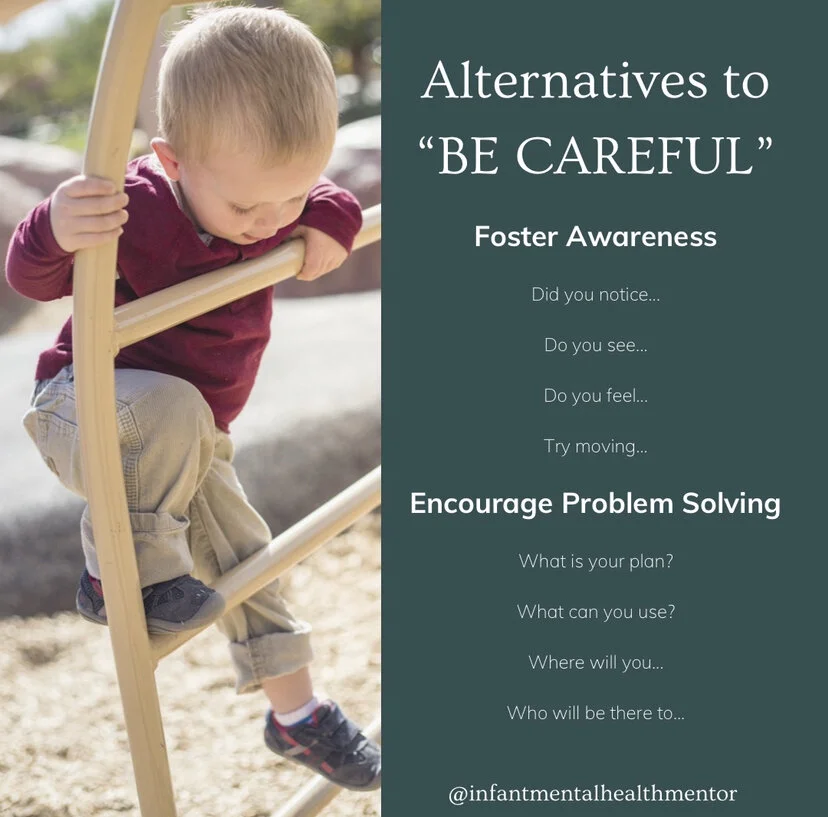

Swap Out “Be Careful”

“Be careful” is not actually very helpful, mostly because of its tendency for overuse and because it is not specific enough. Try practicing phrases that encourage your child to problem solve (“You might think about using your hands to hold on to the side”) or promote awareness of the situations (“Do you notice that those rocks are a bit slippery from the rain?”).

Promoting exploration and risk-taking behavior does not mean we have to ignore our drive to protect and support our children. It just means that we have to find a balance between what we need and what they do. Exploring our fears, knowing their skills, understanding the environment, and making space for learning and growth can offer our children so much. Finding a structured way to take risks gives them reasons to feel confident in their ability to try new things, offers opportunities to learn new skills, and lets our children know that not only do we trust them, but we are there to help them when they need it.